This is an excerpt from a chapter I wrote for the O'Reilly anthology, Creating Augmented and Virtual Realities, edited by Erin Pangilinan, Vasanth Mohan, and Steve Lukas. This section quickly covers the history of I/O for computers, and then discusses current inputs available today.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Modalities Through The Ages

- Pre-20th Century

- Through WWII

- Post-WWII

- The Rise Of Personal Computing

- Computer Miniaturization

- Current Controllers For Immersive Computing Systems

- Body Tracking Technologies

- Hand Tracking.

- Hand Pose Recognition.

- Eye tracking.

- A Note On Hand Tracking And Hand Pose Recognition.

- Voice, Hands, And Hardware Inputs Over The Next Generation

- Voice.

- Hands.

- Hardware Inputs.

Introduction

In the game Twenty Questions, your goal is to guess what object another person is thinking. You can ask anything you want, and they have to answer truthfully; the catch is that they will only answer questions with one of two options: ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Through a series of happenstance and interpolation, the way we communicate with conventional computers is very similar to Twenty Questions. Computers speak in binary, ones and zeroes, and humans do not. Computers have no inherent sense of the world, or indeed anything outside of either the binary—or, in the case of quantum computers, probabilities.

Because of this we communicate everything to computers, from concepts to inputs, through increasing levels of human-friendly abstraction that cover up the basic communication layer: ones and zeroes, or yes and no.

Thus much of the work of computing today is figuring out how to get humans to explain increasingly complex ideas easily and simply to computers. In turn, humans are also working towards having computers process those ideas more quickly, by building those abstraction layers on top of the ones and zeroes. It is a cycle of input and output, affordances and feedback, across modalities. The abstraction layers can take many forms: the metaphors of a graphical user interface, the spoken words of natural language processing, the object recognition of computer vision, and, most simply and commonly, the everyday inputs of keyboard and pointer, with which most humans interact with computers on a daily basis.

Modalities Through The Ages: Pre-20th Century

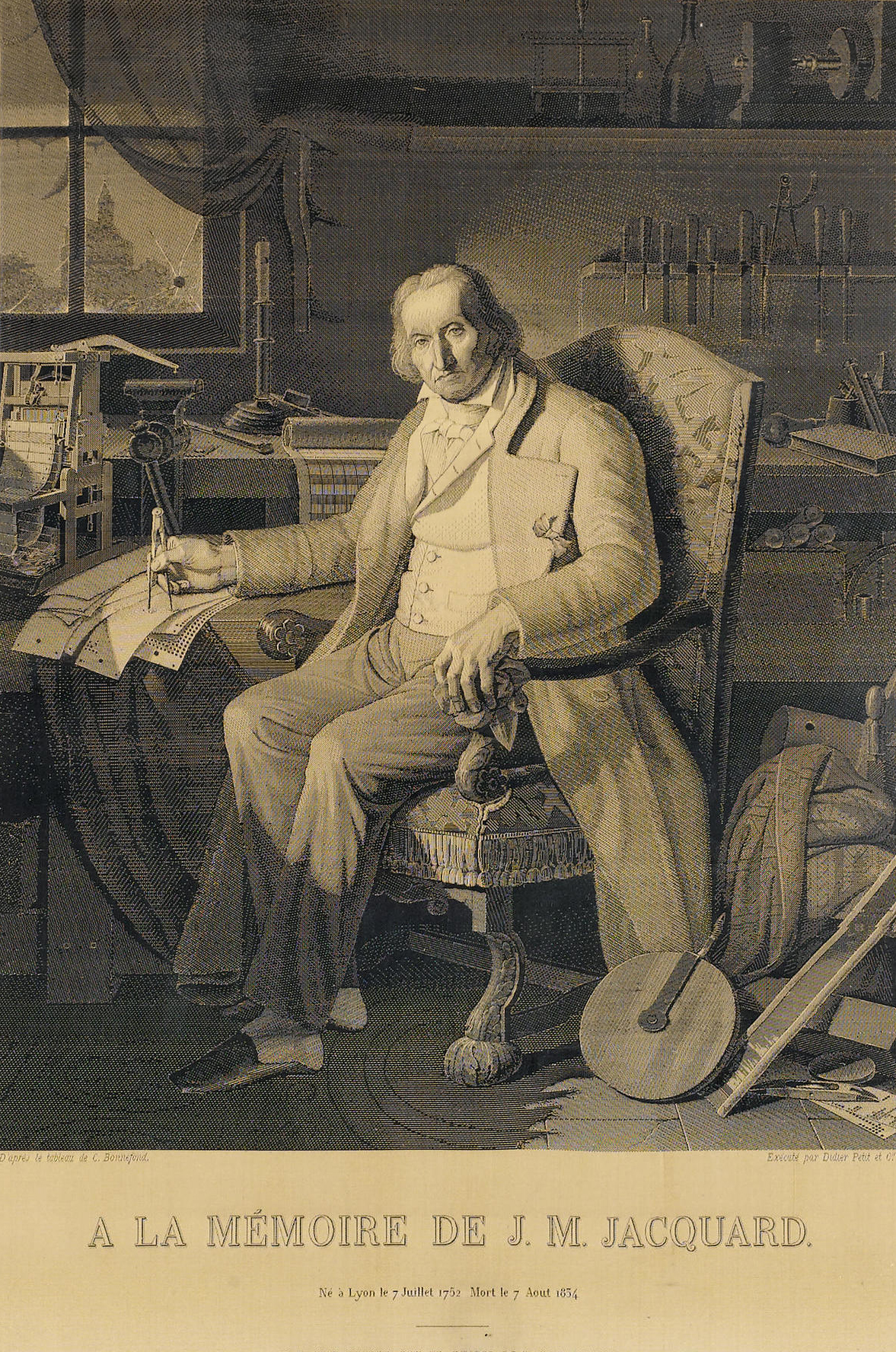

Caption: The woven silk portrait of Joseph Jacquard, 1839. Jacquard used over 24,000 punched cards to create the portrait.

To begin, let’s briefly discuss how humans have traditionally given instructions to machines. The earliest proto-computing machines, the programmable weaving looms, famously ‘read’ punchcards. Joseph Jacquard created what was in effect one of the first pieces of true mechanical art, a portrait of himself, using punchcards in 1839. Around the same time in Russia, Semen Korsakov had realized that punch cards could be used to store and compare datasets.

As mentioned earlier, proto-computers had an equally compelling motivation: computers need very consistent physical data, and it’s uncomfortable for humans to make consistent data. So while it might seem surprising in retrospect, by the early 1800s, punchcard machines, not yet the calculation monsters they would become, already had keyboards attached to them.

Punchards can hold significant amounts of data, as long as the data is consistent enough to be read by a machine. And while pens and similar handheld tools are fantastic for specific tasks, allowing humans to quickly express information, the average human forearm and finger tendons lack the ability to consistently produce near identical forms all the time.

This has long been a known problem. In fact, from the seventeenth century—that is, as soon as the technology was available—people started to make keyboards. [source] People invented and re-invented keyboards for all sorts of reasons: to work against counterfeiting, helping a blind sister, better books. Having a supportive plane against which to rest the hands and wrists allowed for inconsistent movement to yield consistent results that are impossible to achieve with the pen.

Keyboards have been attached to computational devices since the beginning, but of course expanded out to typewriters before looping back again as the two technologies merged. The impetuous was similarly tied to consistency and human fatigue. From Wikipedia: ‘By the mid-19th century, the increasing pace of business communication had created a need for mechanization of the writing process. Stenographers and telegraphers could take down information at rates up to 130 words per minute.’ Writing with a pen, in contrast, only gets you about thirty words a minute: button presses were undeniably the better alphanumeric solution.

Caption: A Masson Mills WTM 10 Jacquard Card Cutter, 1783. These machines were used to create the punched cards read by a Jacquard loom.

Modalities Through The Ages: Through WWII

So much for keyboards, which have been with us since the beginning of humans attempting to talk to their machines. From the early 20th century on—that is, again, as soon as metalwork and manufacturing techniques supported it—we gave machines a way to talk back, to have a dialogue with their operators before the expensive physical output stage: monitors and displays, a field that benefited from significant research and resources through the wartime eras via military budgets.

The first computer displays didn’t show words: early computer panels had small light bulbs that would switch on and off to reflect specific states, allowing engineers to monitor the computer’s status—and leading to the use of the word ‘monitor’. During WWII, military agencies used CRT screens for radar scopes, and soon after the war CRTs began their life as vector, and later text, computing displays for groups like SAGE and the Royal Navy.

As soon as computing and monitoring machines had displays, we had display-specific input to go alongside them. Joysticks were invented for aircraft, but their use for remote aircraft piloting was patented in the USA in 1926.

This demonstrates a curious quirk of human physiology: that we are able to instinctively re-map proprioception—our sense of the orientation and placement of our bodies—to new volumes and plane angles. If we weren’t able to do so, it would be impossible to use a mouse on a desktop on the Z-plane to move the mouse anchor on the X. And yet we can do it almost without thought—although some of us might need to invert the axis rotation to mimic our own internal mappings.

An example of early computer interfaces for proprioceptive remapping. Here, WAAF radar operator Denise Miley is plotting aircraft in the Receiver Room at Bawdsey 'Chain Home' station in May 1945. Notice the large knob to her left, a goniometer control that allowed Miley to change the sensitivity of the radio direction finders.

Modalities Through The Ages: Post-WWII

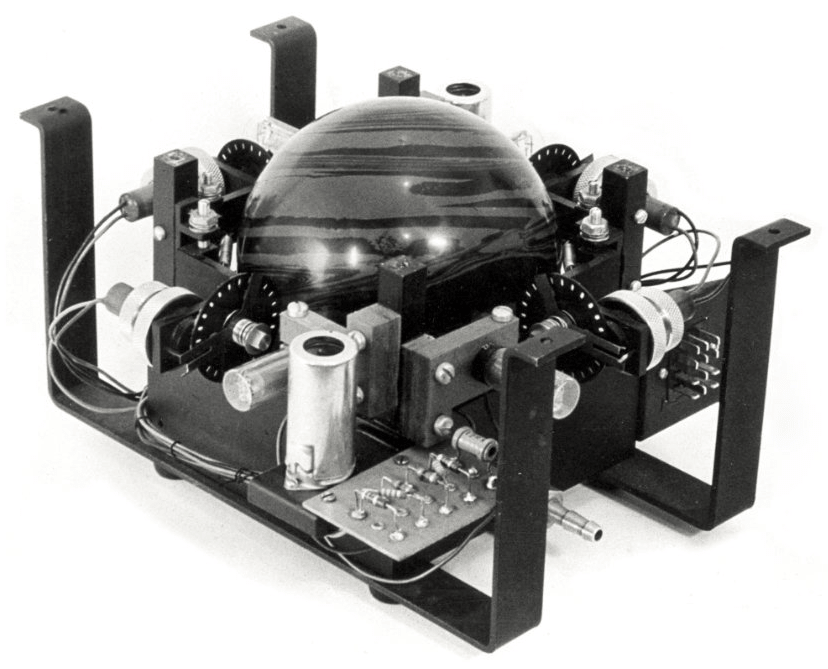

Joysticks quickly moved out of airplanes and alongside radar and sonar displays during WWII. Immediately after the war, in 1946, the first display-specific input was invented. Ralph Benjamin, an engineer in the Royal Navy, conceived of the rollerball as an alternative to the existing joystick inputs: “The elegant ball-tracker stands by his aircraft direction display. He has one ball, which he holds in his hand, but his joystick has withered away.” [source] The indication seems to be that the rollerball could be held in the hand, rather than set on a desk. However, the reality of manufacturing in 1946 meant that the original roller was a full-sized bowling ball. Unsurprisingly, the unwieldy, ten-pound rollerball did not replace the joystick.

The five rules of

computer input success

In order to take off, inputs must be:

- Cheap

- Reliable

- Comfortable

- Have software that makes use of it, and

- Have an acceptable user error rate.

This leads us to the five rules of computer input popularity. In order to take off, inputs must be:

- Cheap

- Reliable

- Comfortable

- Have software that makes use of it, and

- Have an acceptable user error rate.

The last can be amortized by good software design that allows for non-destructive actions, but beware: after a certain point, even benign errors can be annoying. Autocorrect on touchscreens is a great example of user error often overtaking software capabilities.

Even though the rollerball mouse wouldn’t reach ubiquity until 1984, with the rise of the personal computer, many other types of inputs that were used with computers moved out of the military through the mid-1950s and into the private sector: joysticks, buttons and toggles, and of course the keyboard.

It might be surprising to learn that styluses predated the mouse. The light pen or gun, created by SAGE in 1955, was an optical stylus that was timed to CRT refresh cycles and could be used to interact directly on monitors. Another mouse-like option, the Data Equipment Company’s Grafacon, resembled a block on a pivot that could be swung around to move the cursor. There was even work done on voice commands as early as 1952, with Bell Labs’ Audrey system, though it only recognized ten words.

Sketchpad demo, 1964.

By 1963, the first graphics software existed that allowed users to draw on the MIT Lincoln Laboratory TX-2’s monitor: Sketchpad, created by Ivan Sutherland at MIT. GM and IBM had a similar joint venture, the Design Augmented by Computer or DAC-1, which used a capacitance screen with a metal pencil instead—faster than the light pen, which required waiting for the CRT to refresh.

Unfortunately, in both the light pen and metal pencil case, the displays were upright and thus the user had to hold up their arm for input, the infamous ‘gorilla arm’. Great workout, but bad ergonomics. The RAND corporation had noticed this problem and had been working on a tablet-and-stylus solution for years, but it wasn’t cheap: in 1964, the RAND stylus—later also marketed as the Grafacon, confusingly—cost around $18,000 USD (roughly $150k in 2018 USD). It was years before the tablet-and-stylus combination would take off, well after the mouse and graphical user interface (GUI) system had been popularized.

In 1965, Eric Johnson, of the Royal Radar Establishment, published a paper on capacitive touchscreen devices, and spent the next few years writing more clear use cases on the topic. It was picked up by CERN researchers, who created a working version by 1973.

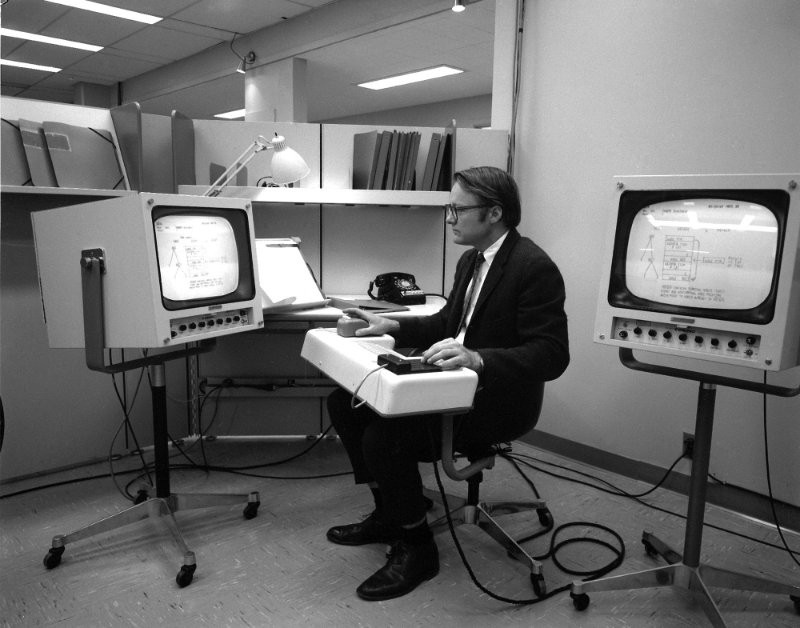

By 1968, Doug Engelbart was ready to show the work that his lab, the Augmentation Research Center, had been doing at Stanford Research Institute since 1963. In a hall under San Francisco’s Civic Center, he demonstrated his team’s oNLine System (NLS) with a host of features now standard in modern computing: version control, networking, videoconferencing, multimedia emails, multiple windows, and working mouse integration, among many others. Although the NLS also required a chord keyboard and conventional keyboard for input, the mouse is now often mentioned as one of the key innovations. In fact, the NLS mouse ranked similarly useable to the light pen or ARC’s proprietary knee input system in Engelbart’s team's own research [source] .

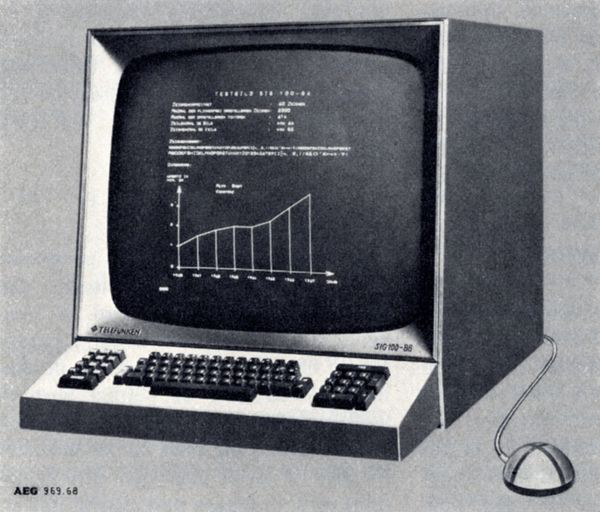

Nor was it unique: Telefunken released a mouse with their RKS 100-86, the Rollkugel, which was actually in commercial production the year Engelbart announced his prototype. [source]

However, Engelbart certainly popularized the notion of the asymmetric freeform computer input. The actual designer of the mouse at ARC, Bill English, also pointed out one of the truths of digital modalities at the conclusion of his 1967 paper, ‘Display-Selection Techniques for Text Manipulation’. “[I]t seems unrealistic to expect a flat statement that one device is better than another. The details of the usage system in which the device is to be embedded make too much difference.” No matter how good the hardware is, the most important aspect is how the software interprets the hardware input and normalizes for user intent.

For more on how software design can affect user perception of inputs, I highly recommend the book "Game Feel: A Game Designer's Guide to Virtual Sensation" by Steve Swink. Because each game has its own world and own system, the ‘feel’ of the inputs can be rethought. There is less wiggle room for innovation in standard computer operating systems, which must feel familiar by default to avoid cognitive overload.

Demonstration of the NLS system.

From OldMouse.com: "The SIG-100 illustration in the October 1968 of the Telefunken company magazine with the Rollkugel "mouse" attached. Apparently the button was added later."

Another aspect of tech advances worth noting from the 1960s was the rise of science fiction, and therefore computing, in popular culture. TV shows like Star Trek (1966-1969) had voice commands, telepresence, smart watches and miniature computers. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969) showed a small personal computing device that looks remarkably similar to the iPads of today, as well as voice commands, video calls, and, of course, a very famous AI. The Jetsons (1962-1963) had smart watches, as well as driverless cars and robotic assistance. Although the tech wasn’t common or even available, people were being acclimated to the idea that computers would be small, lightweight, versatile, and have uses far beyond text input or calculations.

The 1970s was the decade just before personal computing. Home game consoles started being commercially produced in the 70s, and arcades took off. Computers were increasingly affordable; available at top universities, and more common in commercial spaces. Joysticks, buttons and toggles easily made the jump to video game inputs and began their own, separate trajectory as game controllers. Xerox PARC began work on an integrated mouse and graphical user interface computer work system called the Alto. The Alto and its successor, the Star, were highly influential for the first wave of personal computers manufactured by Apple, Microsoft, Commodore, Dell, Atari and others in the early-to-mid 1980s. PARC also created a prototype of Alan Kay’s 1968 KiddiComp/Dynabook, one of the precursors of the modern computer tablet.

Modalities Through The Ages:

The Rise Of Personal Computing

Often, people think of the mouse and GUI as a huge and independent addition to computer modalities. But even in the 1970s, Summagraphics was making both low-and high-end tablet-and-stylus combinations for computers [source], one of which was white labeled for the Apple II as the Apple Graphics Tablet [source], released in 1979. It was relatively expensive, and only supported by a few types of software; violating two of the five rules. By 1983, HP had released the HP-150, the first touchscreen computer. However, the tracking fidelity was quite low, violating the user error rule.

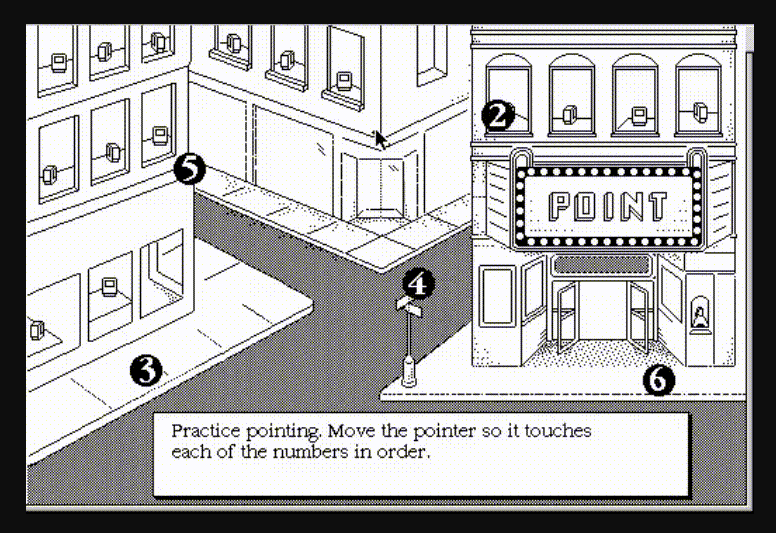

When the mouse was first bundled with personal computer packages (1984-1985), it was supported on the operating system level, which in turn was designed to take mouse input. This was a key turning point for computers: the mouse was no longer an optional input, but an essential one. Rather than a curio or optional peripheral, computers were now required to come with tutorials teaching users how to use a mouse—similar to how video games include a tutorial, teaching players how the game’s actions map to the controller buttons.

Frame from an early Macintosh mouse tutorial.

It’s easy to look back on the 1980s and think the personal computer was a standalone innovation. But in general, there are very few innovations in computing that single-handedly moved the field forward in less than a decade. Even the most famous innovations, such as FORTRAN, took years to popularize and commercialize. Much more often, the driving force behind adoption—what feels to people like a new innovation—is simply the result of the technology finally fulfilling the five rules: cheap, reliable, comfortable, have software that makes use of the tech, and having an acceptable user error rate.

Note: It is very common to find that the first version of what appears to be recent technology was in fact invented decades or even centuries ago. If the technology is obvious enough that multiple people try to build it, but it still doesn’t work, it is likely failing in one of the five rules. It will simply have to wait until technology improves, or manufacturing processes catch up.

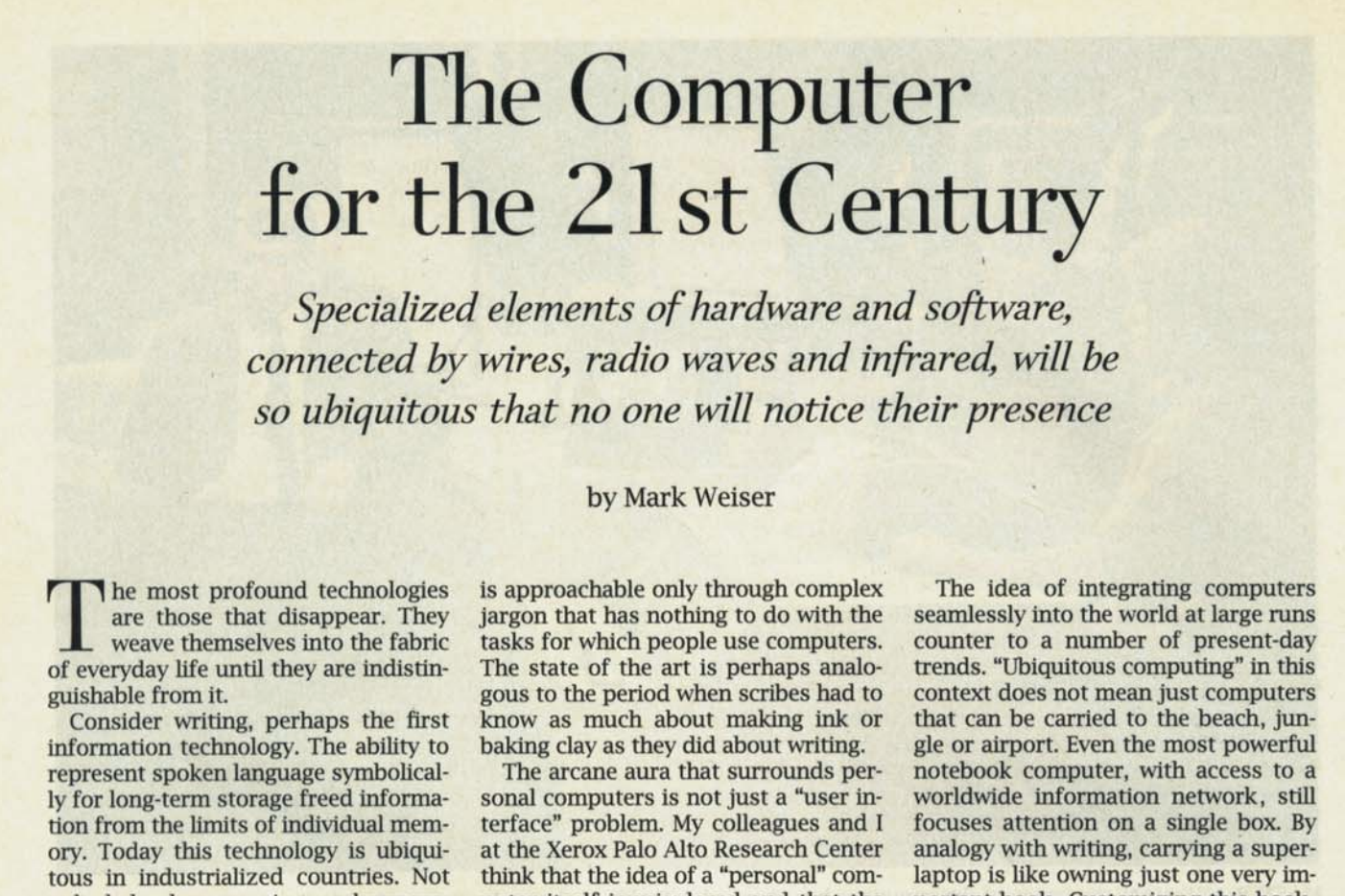

This truism is of course exemplified in virtual and augmented reality history. Although the first stereoscopic head-mounted displays (HMDs) were pioneered by Ivan Sutherland in the 1960s and used at NASA routinely since the 1990s, it wasn’t until the fields of mobile electronics and powerful GPUs improved enough to make the technology available at a commercially acceptable price, decades later. Even as of today, high-end standalone HMDs are either thousands of dollars, or not commercially available. But much like smart phones in the early 2000s, we can see a clear path from current hardware to the future of spatial computing.

However, before we dive in to today’s hardware, let’s finish laying out the path from the PCs of the early 1980s to the most common types of computer today: the smartphone.

Modalities Through The Ages:

Computer Miniaturization

Computers with miniaturized hardware emerged out of the calculator and computer industries as early as 1984 with the Psion Organizer. The first successful tablet computer was the GriDPad, released in 1989, whose VP of research Jeff Hawkins later went on to found the Palm Pilot. Apple released the Newton in 1993, which had a handwritten character input system, but it never hit major sales goals. The project ended in 1998 as the Nokia 900 Communicator —a combination telephone and PDA—and later the Palm Pilot dominated the miniature computer landscape. Diamond Multimedia released their Rio PMP300 MP3 player in 1998 as well, a surprise hit during the holiday seasons. This lead to the rise of other popular MP3 players: mostly noteably, iRiver, Creative NOMAD, and of course, the Apple iPod.

In general, PDAs tended to have stylus and keyboard inputs; more single-use devices, like music players, had simple button inputs. From almost the beginning of their manufacturing, the Palm Pilots shipped with their handwriting recognition system, Graffiti, and by 1999 the Palm VII had network connectivity. The first Blackberry came out the same year with keyboard input, and by 2002 Blackberry had a more conventional phone and PDA combo device.

But these tiny computers didn’t have the luxury of human-sized keyboards. This not only pushed the need for better handwriting recognition, but also real advances in speech input. Dragon Dictate came out in 1990 and was the first consumer option available—though for $9,000, it violated the ‘cheap’ rule heavily. AT&T rolled out voice recognition for their call centers by 1992. Lernout & Hauspie acquired several companies through the 1990s and was used in Windows XP. After an accounting scandal, they were bought by SoftScan—later Nuance, which was licensed as the first version of Siri.

In 2003, Microsoft launched Voice Command for their Windows Mobile PDA. By 2007, Google had hired away some Nuance engineers and were well on their way with their own voice recognition technology. Through today, voice technology is increasingly ubiquitous, with most platforms offering or developing their own technology, especially on mobile devices. It’s worth noting that in 2018, there is no cross-platform or even cross-company standard for voice inputs: the modality is simply not mature enough yet.

PDAs, handhelds and smart phones have almost always been interchangeable with some existing technology since their inception—calculator, phone, music player, pager, messages display, or watch. In the end, they are all simply different slices of computer functionality. One can therefore think of the release of the iPhone in 2007 as a turning point for the small computer industry: by 2008, Apple had sold 10 million more than the next top-selling device, the Nokia 2330 classic, even though the Nokia held steady sales of 15 million from 2007-2008. The iPhone itself did not take over iPod sales until 2010, after Apple allowed users to fully access iTunes.

One very strong trend with all small computers devices, whatever the brand, is the move towards touch inputs. There are several reasons for this.

- The first is simply that visuals are both inviting and useful, and the more we can see, the higher the perceived quality of the device is. With smaller devices, space is at a premium, and so removing physical controls from the device means a larger percentage of the device is a display.

- The second and third are practical and manufacturing-focused. As long as the technology is cheap and reliable, the less moving parts means less production cost and less mechanical breakage, both enormous wins for hardware companies.

- The fourth is that using one's hands as an input is perceived as natural. Although it doesn’t allow for minute gestures, a well-designed, simplified GUI can work around many of the problems that come up around user error and occlusion. Much like the shift from keyboard to mouse-and-GUI, new interface guidelines for touch allow a reasonably consistent and error-free experience for users that would be almost impossible using touch with a mouse or stylus-based GUI.

- The final reason is simply a matter of taste: current design trends are tending towards minimalism in an era when computer technology can be overwhelming. Thus a simplified device can be perceived as easier to use, even if the learning curve is much more difficult and features are removed.

One interesting connection point between hands and mice is the trackpad, which in recent years has the ability to mimic the multi-touch gestures of touchpad while avoiding the occlusion problems of hand-to-display interactions. Because the tablet allows for relative input that can be a ratio of the overall screen size, it allows for more minute gestures, akin to a mouse or stylus. It still retains several of the same issues that plague hand input—fatigue and lack of the physical support that allows the human hand to do its most delicate work with tools—but it is useable for almost all conventional OS-level interactions.

Current Controllers For Immersive Computing Systems

The most common type of controller, across all XR platforms, owes its roots to conventional game controllers. It is very easy to trace any given commercial XR HMD’s packaged controllers back to the design of the multi-joystick-and-d-pad. Early work around motion tracked gloves, such as NASA Ames’ VIEWlab from 1989, has not yet been commoditized at scale. Funnily enough, Ivan Sutherland had posited that VR controllers should be joysticks back in 1964; almost all have them, or thumbpad equivalents, in 2018.

Before the first consumer headsets, Sixsense was an early mover in the space with its magnetic, tracked controllers, which included buttons on both controllers familiar to any game console: A and B, home, as well as more genericized buttons, joysticks, bumpers, and triggers.

The Sixsense Stem input system.

Current fully tracked, PC-bound systems have similar inputs. The Oculus Rift controllers, Vive controllers, and Windows MR controllers all have the following in common:

- a primary select button (almost always a trigger),

- a secondary select variant (trigger, grip, or bumper),

- A/B button equivalents;

- a circular input (thumbpad, joystick, or both), and

- several system-level buttons, for consistent basic operations across all applications.

- Generally these last are used to call up menus and settings, and leave apps to return to the home screen.

Standalone headsets have some subset of the above in their controllers. From the untracked Hololens remote to the Google Daydream’s three degrees freedom (3DOF) controller, you will always find the system-level buttons that can perform the following actions: confirm, and return to the home screen. Everything else depends on the capabilities of the HMD’s tracking system and how the OS has been designed.

Although technically raycasting is a visually tracked input, most people will think of it as a physical input, so it does bear mentioning here. For example, the Magic Leap controller allows for selection both with raycast from the 6DOF controller and from using the thumbpad, as does the Rift in certain applications, like their avatar creator. But as of 2019 there is no standardization around raycast selection vs analog stick or thumbpad.

As tracking systems improve and standardize, we can expect this standard to solidify over time. Both are useful at different times, and much like the classic Y-axis inversion problem, it may be that different users have such strongly different preferences that we should always allow for both. Sometimes you want to point at sometime to select it; sometimes you want to scroll over to select it. Why not both?

Body Tracking Technologies

Let’s go through the three most common discussed types of body tracking today:

Hand Tracking.

Hand tracking is when the entire movement of the hand is mapped to a digital skeleton and input inferences are made based on the movement or pose of the hand. This allows for natural movements like picking up and dropping of digital objects and gesture recognition. Hand tracking can be entirely computer vision based, include sensors attached to gloves, or use other types of tracking systems.

Hand Pose Recognition.

This concept is often confused with hand tracking, but hand pose recognition is its own specific field of research. The computer has been trained to recognize specific hand poses, much like sign language. The intent is mapped when when each hand pose is tied to specific events, like grab, release, select, and other common actions.

On the plus side, pose recognition can be less processor-intensive and need less individual calibration than robust hand tracking. But externally, it can be tiring and confusing to users who might not understand that the pose recreation is more important than natural hand movement. It also requires a significant amount of user tutorials to teach hand poses.

Eye tracking.

The eyes are constantly moving, but tracking their position makes it much easier to infer interest and intent—sometimes even more quickly than the user knows themselves, since eye movements update before the brain visualization refreshes. While it’s quickly tiring as an input in and of itself, eye tracking is an excellent input to mix with other types of tracking. For example, it can be used to triangulate the position of the object an user is interested in, in combination with hand or controller tracking, even before the user has fully expressed an interest.

***

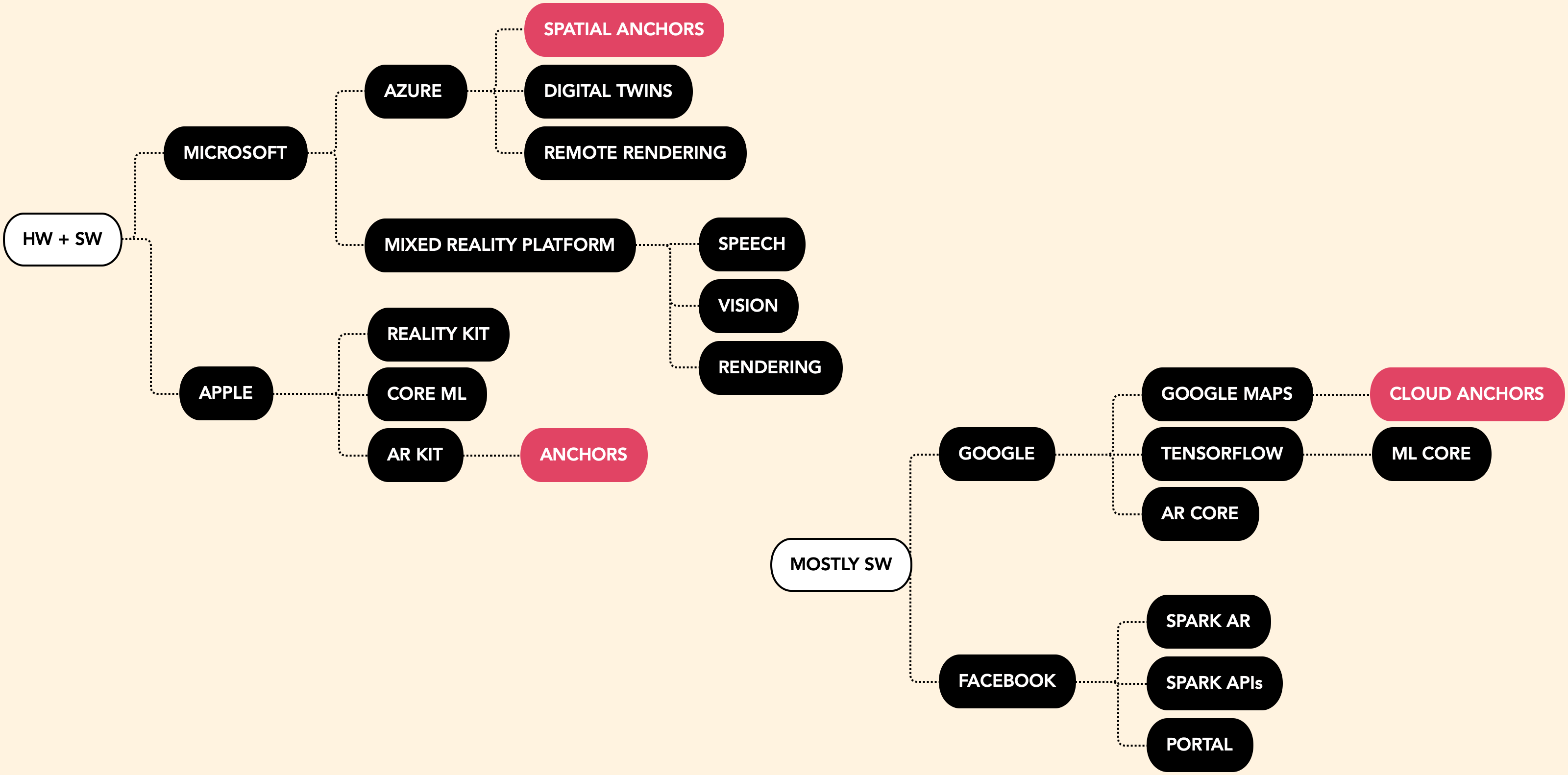

I’m not yet including body tracking or speech recognition on the list, largely because there are no technologies on the market today that are even beginning to implement either tech as a standard input technique for XR. But companies like Leap Motion, Magic Leap, and Microsoft are paving the way for all of the nascent tracking types listed here.

A Note On Hand Tracking And Hand Pose Recognition.

Hand tracking and hand pose recognition both must result in interesting, and somewhat counterintuitive, changes to how humans often think of interacting with computers. Outside of conversational gestures, in which hand movement largely plays a supporting role, humans do not generally subscribe a significance to the location and pose of their hands. We use hands every day as tools and can recognize a mimicked gesture for the action it relates to, like picking up an object. Yet in the history of human-computer interaction hand location means very little. In fact, peripherals like the mouse and the game controller are specifically designed to be hand-location agnostic: you can use a mouse on the left or right side, you can hold a controller a foot up or down in front of you, and it makes no difference to what you input.

The glaring exception to this rule is touch devices, in which hand location and input are necessarily tightly connected. Even then, touch ‘gestures’ have little to do with hand movement outside of the fingertips touching the device; you can do a three-finger swipe with any three fingers you choose. The only really important thing is that you fulfill the minimum requirement to do what the computer is looking for to get the result you want.

Computer vision that can track hands, eyes, and bodies is potentially extremely powerful, but can be misused.

Voice, Hands, And Hardware Inputs Over The Next Generation

If you were to ask most people on the street, the common assumption is that we will ideally, and eventually, interact with our computers the way we interact with other humans: by talking normally and using our hands to gesture and interact. Many, many well-funded teams across various companies are working on this problem today, and both of those input types will surely be perfected in the coming decades. However, they both have significant drawbacks that people don’t often consider when they imagine the best-case scenario of instant, complete hand tracking and natural language processing.

Voice.

In common vernacular voice commands aren’t precise, no matter how perfectly understood. People often misunderstand even plain language sentences, and often others use a combination of inference, metaphor, and synonyms to get their real intent across. In other words: they use multiple modalities, and modalities within modalities, to make sure they are understood. Jargon is an interesting linguistic evolution of this: highly specialized words that mean a specific thing in a specific context to a group are a form of language hotkey, if you will.

Computers can react much more quickly than humans can—that is their biggest advantage. To reduce input to mere human vocalization means we significantly slow down how we can communicate with computers from today. Typing, tapping, and pushing action-mapped buttons are all very fast and precise. For example, it is much faster to select a piece of text, hit the hotkeys for ‘cut’, move the cursor, and hit the hotkeys for ‘paste’ than it is to describe those actions to a computer. This is true of almost all actions.

However to describe a scenario, tell a story, or make a plan with another human, it’s often faster to simple use words in conversations as any potential misunderstanding can be immediately questioned and course-corrected by the listener. This requires a level of working knowledge of the world that computers will likely not have until the dawn of true artificial intelligence.

There are other advantages to voice input: when you need hands-free input, when you are otherwise occupied, when you need transliteration dictation, or when you want a fast modality switch (eg, “minimize! exit!”) without other movement. Voice input will always work best when it is used in tandem with other modalities, but that’s no reason it shouldn’t be perfected. And of course, voice recognition and speech-to-text transcription technology has use beyond mere input.

Hands.

Visual modalities like hand tracking, gestures, and hand pose recognition are consistently useful as a secondary confirmation, exactly the same way they are useful as hand and posture poses in regular human conversation. They will be most useful for spatialize computing when we have an easy way to train up personalized datasets for individual users very quickly. This will require a few things:

- Individuals to maintain personalized biometric datasets across platforms, and

- A way for individuals to teach computers what they want them to notice or ignore.

The reasons for these requirements is simple: humans vary wildly both in how much they move and gesture, and what those gestures mean to them. One person may move their hands constantly, with no thought involved. Another may only gesture occasionally, but that gesture has enormous importance. We not only need to customize these types of movements broadly per-user, but also allow the user themselves to tell the computer what it should pay special attention to and what it should ignore.

The alternative to personalized, trained systems is largely what we have today: a series of predefined hand poses that are mapped specifically to certain actions. For Leap Motion, a ‘grab’ pose indicates the user wants to select and move an object. For the Hololens, the ‘pinch’ gesture indicates selection & movement. The Magic Leap supports ten hand poses, some of which map to different actions in different experiences. The same is true of the Oculus Rift controllers, which support two hand poses (point, and thumbs up) both of which can be remapped to actions of the developers’ choice.

This requires the user to memorize the poses and gestures required by the hardware instead of a natural hand movement, much like how tablet devices standardized swipe-to-move and pinch-to-zoom. While these types of human-computer sign language do have the potential to standardize and become the norm, proponents should recognize that what they propose is an alternative to how humans use their hands today, not a remapping. This is especially exacerbated by the fact that human hands are imprecise on their own; they require physical support and tools to allow for real precision.

The alternative to personalized, trained systems is largely what we have today: a series of predefined hand poses that are mapped specifically to certain actions. For Leap Motion, a ‘grab’ pose indicates the user wants to select and move an object. For the Hololens, the ‘pinch’ gesture indicates selection & movement. The Magic Leap supports ten hand poses, some of which map to different actions in different experiences. The same is true of the Oculus Rift controllers, which support two hand poses (point, and thumbs up) both of which can be remapped to actions of the developers’ choice.

This requires the user to memorize the poses and gestures required by the hardware instead of a natural hand movement, much like how tablet devices standardized swipe-to-move and pinch-to-zoom. While these types of human-computer sign language do have the potential to standardize and become the norm, proponents should recognize that what they propose is an alternative to how humans use their hands today, not a remapping. This is especially exacerbated by the fact that human hands are imprecise on their own; they require physical support and tools to allow for real precision.

Triangulation to support hand weight is important—even if you have a digital sharp edge or knife, you need to have a way to support your hand for more minute gestures.

Hardware inputs.

As we saw in the introduction, there has been a tremendous amount of time and effort put into creating different types of physical inputs for computers for almost an entire century. However, due to the five rules, peripherals have standardized. Of the five rules, two are most important here: it is cheaper to manufacture at scale, and inputs have standardized alongside the hardware that supports them.

However, we are now entering an interesting time for electronics. For the first time, it’s possible for almost anyone to buy or make their own peripherals that can work with many types of applications. People make everything out of third-party parts: from keyboards and mice, to Frankenstien-ed Vive trackers on top of baseball bats or pets, and custom paint jobs for their xBox controllers.

It’s a big ask to assume that because spatial computing will allow for more user customization, that consumers would naturally start to make their own inputs. But it is easy to assume that manufacturers will make more customized hardware to suit demand. Consider automobiles today: the Lexus 4 has over 450 steering wheel options alone, and with all options put together, allows for four million combinations of the same vehicle. When computing is personal and lives in your house alongside you, people will have strong opinions about how it looks, feels, and reacts, much as they do with their vehicles, their furniture, and their wallpaper.

This talk of intense customization, both on the platform side and on the user side, leads us to a new train of thought: spatial computing allows computers to be as personalized and varied as the average person’s house and how they arrange the belongings in their house. The inputs therefore need to be equally varied. The same way someone might choose one pen versus another pen to write will apply to all aspects of computer interaction.