BEYOND UI:

GOOD DESIGN FEEL

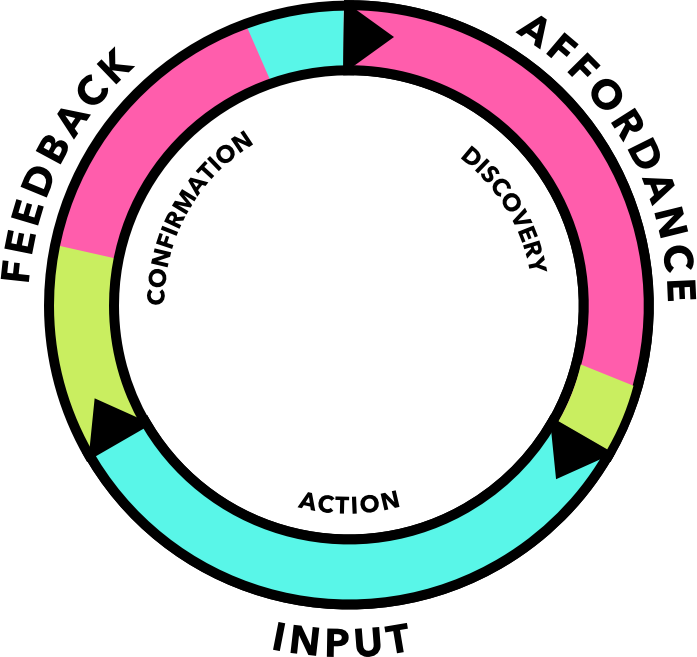

In all digital design, the interactions should be respectful, comfortable, and cover a wide variety of sensory input to cover user intent and context. In virtual & augmented reality, this means treating the user interface with the same care and attention you'd give to an animated character. Here's a list of examples.

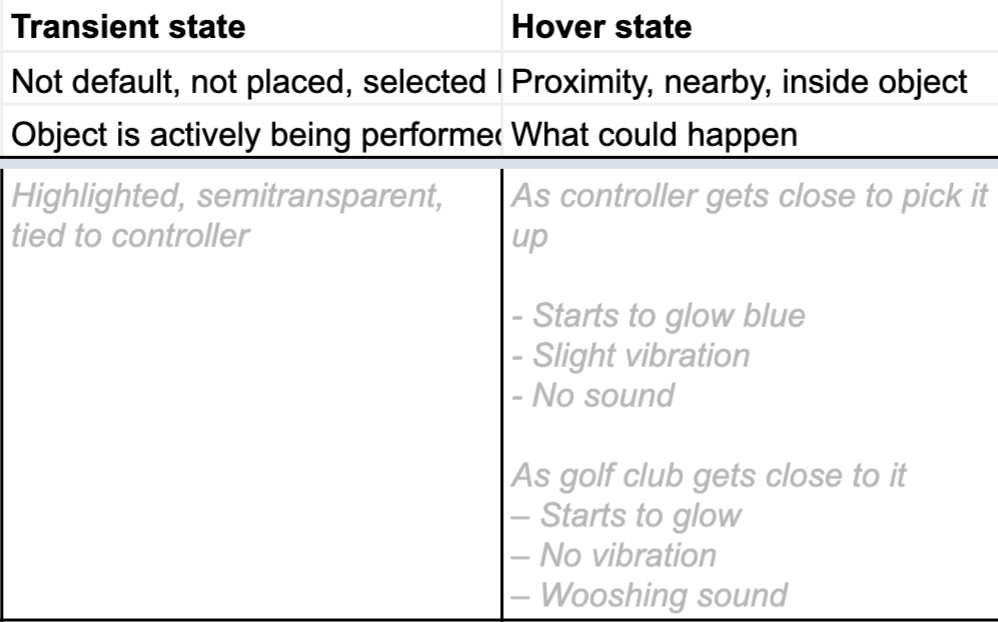

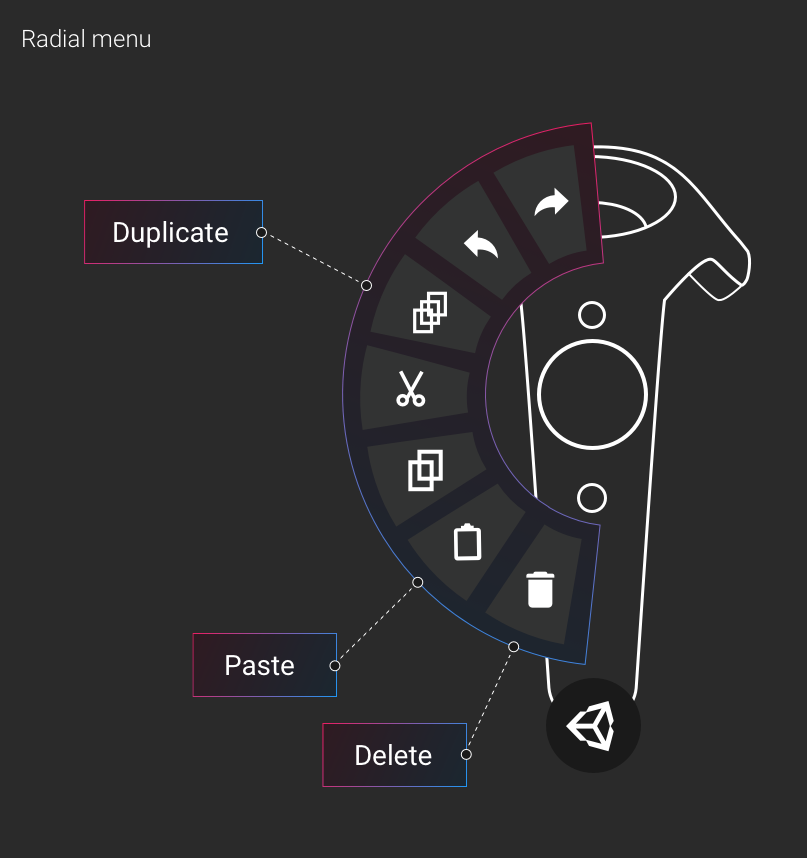

OPEN AND CLOSE

In the same way objects don't suddenly disappear or appear in real life, digital objects must join and leave us in a way we can comprehend, and that feels comfortable. The treatment can be quicker and more elegant than physically possible, but we've learned objects simply must have some transition state in order for humans to even notice them. For EditorXR and the MARS companion apps, we use a combination: scale and movement , haptics, and sound.

SIZE

Size has four main considerations in XR: user comfort, display resolution, field of view, and finally, digital or real environment. Unfortunately, these extremely practical considerations leave aesthetics in a firm fifth place. A beautifully constructed piece of UI is of no use if it is stuck in a wall, unbearably large, or outside the FOV.

DISTANCE

Tightly connected to size, distance has very similar considerations, but user comfort comes to the forefront. This can be based on height or size, but also social norms and personal preference.

MOVEMENT

Movement is deeply tied to the levels of realism, and even the personality, you can give to your UI. Is it a part of your real or digital world, or can it pass through them, ignoring meshes or colliders? Does it react to objects, making space for new ones? Does it follow you, or maintain a fixed position? If you call it to you, does it come running, or leisurely glide over?

SOUND

Sound design plays an even deeper role than movement for both personality and realism. Sound is both an indication of physical events—in some cases, a proxy for haptics—and also a language in and of itself. Humans can memorize sounds unconciously and extremely quickly; this is extraodinarily useful, especially when used subtly for prompt, confirmation or error cues that don't need visual interruption or other sensory input.

HAPTICS

Haptics, like sound, are the best way to provide user feedback without interrupting flow. In fact, one can easily, and rightfully, argue that sounds are simply a subset of haptics. Haptics often are discussed in terms of controller vibration, but the hardware design itself, from the button travel to input placement to material texture, all fall under haptics in the user journey.

One thing we've learned from designing our XR tools at Unity is that proxemics can give us general guidelines, but the reality is that down to the last centimeter, humans feel differently about how they want their UI to behave. As a result, we have decided to make all UI animations, distances, and haptics strength customizable via settings in our XR HMD tools. It's a teaching moment for developers, and allows a level of context and comfort for the end user that is essential to good XR design.